The World According to Men

Why it’s so important to have more women doing global-affairs reporting

ISTANBUL—For most of the 19th and 20th centuries, women war correspondents were rare creatures—considered intellectual oddities, more likely to be fetishized than taken seriously as news gatherers.

Even as recently as 2002, Vanity Fair was delighting in the exoticism of such women in its story “Girls at the Front,” which profiled the battle-hardened correspondents Christiane Amanpour, Janine di Giovanni, and Marie Colvin. They had sex appeal and well-furnished London homes, and they made up a small brigade of female journalists jetting off to “whatever hellhole leads the news.”

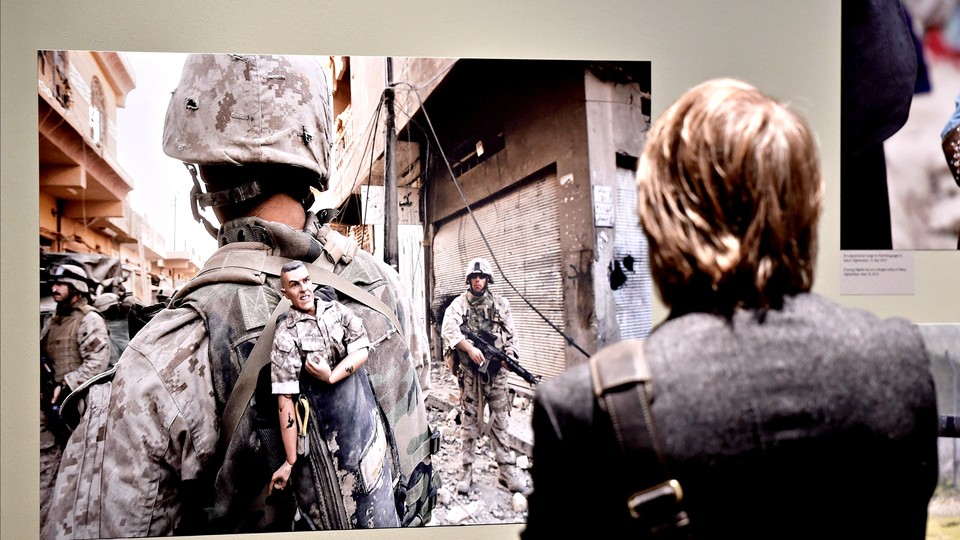

These days, there are so many “girls at the front” that it’s not a story anymore. The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Associated Press all have female bureau chiefs reporting on ISIS, Syria, Yemen, Egypt, and Libya. In Istanbul, a jumping-off point for covering the region, there seem to be more women freelance correspondents than men. This month’s new film Whisky Tango Foxtrot, in which Tina Fey plays an adrenaline-addicted reporter in Afghanistan, captures how women have broken into the tightly knit, elite foreign-correspondents’ club.

Yet the landscape hasn’t entirely changed. When it comes to winning prizes for their work, for example, female foreign correspondents are stuck in the last century. Ample research moreover points to persistent gender bias across television and print media. In 2011, men penned nearly 80 percent of the op-eds published in most major U.S. newspapers; during America’s 2012 elections, male reporters had more than twice as many front-page bylines in major newspapers as women did. In 2015, men also made up around three-fourths of the guests booked to discuss foreign policy and national security on prime-time cable and top Sunday news shows. Even in articles about birth control, abortion, and other topics relating to women’s bodies, men are quoted more frequently.

How journalists portray the world has real consequences, and the world is being portrayed through a male lens.

When my organization, the Fuller Project for International Reporting, which does multimedia reporting on women in conflict and foreign affairs, analyzed journalism awards recently, we found that male correspondents were recognized and rewarded for their reporting nearly two and a half times more often than their female colleagues among the prizes we studied. Consider this: In the last two decades, even as more women have broken into the field, men still won nearly three times as many Pulitzers as women for foreign reporting. Since the mid-1990s, Britain’s prestigious Foreign Reporter of the Year, which is given out at the British Press Awards, has gone 17 times to men and eight times to women. In the last decade, the Robert Capa Gold Medal Award for photojournalism has been given to nine different men and only one woman.

This trend continues. In the last two years, the Overseas Press Club of America has given 50 awards to men but only 21 to women. The George Polk Awards for international, foreign, and war reporting do little better: They went to 29 men and 16 women over the last decade. Ironically, one of the worst discrepancies occurred in the case of the Martha Gellhorn Prizes, named in honor of the most famous female war correspondent of the 20th century. The organization has awarded prizes to 19 men but only to four women. So even as more women are risking their lives to report on the world, their work is still given less weight.

Prizes signal what the industry values. Efforts to win them can drive decisions on which reporters are funded and for which types of projects. Repeatedly awarding men’s reporting over women’s feeds a cycle that perpetuates the relative authority of men’s voices over women’s. Male journalists quoted four times as many men as women in a study of 352 front-page New York Times stories in the first two months of 2013. (The same study found that female journalists also quoted men more frequently than women, but the imbalance was not as severe.) The imbalance in awards also reinforces the notion that reporting on combat, mission strategy, and violent conflict qualifies as “hard news,” while coverage of human rights, maternal health, sexual assault, and education—which women more frequently cover—is “soft” news.

When this male-dominant reporting happens in countries where women already lack a sturdy platform to speak from, the media perpetuates a cycle of invisibility, reinforcing rather than challenging male domination.This has dire consequences. A growing body of research, led by women at Texas A&M University, is proving that countries that suppress women are more violent, more likely to start conflicts, and more likely to let those conflicts to spiral into brutality.

Still, rather than reflect a diversity voices, only “13 percent of stories in the news media on peace- and security-related themes included women as the subject,” according to the UN. Only 4 percent portrayed women as leaders in conflict and post-conflict countries. Only 2 percent highlighted gender equality issues at all.

So it’s a pressing imperative that foreign correspondents to do a more thorough job of including all the voices of people in the countries they cover—and for media management to reward that effort by giving more weight to stories by and about women. Some of the most memorable reporting in recent years has come from women journalists: Rania Abouzeid of The New Yorker has investigated the rise in forced prostitution in Iraq; Alissa Rubin wrote a two-part series in 2015 on wasteful U.S. spending on women in Afghanistan. Rukmini Callimachi exposed ISIS’s twisted interpretation of the Koran to justify rape. Female photographers are also enriching our understanding of how women experience the world. Examples include Stephanie Sinclair’s 10-year project on child brides, Erin Trieb’s images of Kurdish female fighters, and Lynsey Addario’s work on African women dying from routine procedures in childbirth.

Perhaps the female reporter who best exemplifies the difference women journalists can make is The Boston Globe’s Elizabeth Neuffer, who brought attention to Bosnian rape camps in the 1990s and whose reporting played a pivotal role in the decision by the International Tribunal at the Hague to formally designate rape as a crime against humanity.

Neuffer was killed in a car accident in Iraq in 2003. And she isn’t the only female correspondent who has died while reporting from a war zone. Marie Colvin, a subject of Vanity Fair’s article, was killed in a shelling attack in Homs, Syria, in 2012. Syrian citizen journalist Ruqia Hassan, and the Mexican crime reporter Anabel Flores Salazar were both murdered earlier this year for their intrepid journalism.

Women reporters don’t only report on women, of course. Robin Wright of The New Yorker, Jamie Tarabay at Vocativ, Anne Barnard at The New York Times, and Holly Williams at CBS are just a few female reporters whose daily work is just as likely to analyze battle strategies and national security. And Nicholas Kristof, Steve Stecklow, and Kevin Sullivan, among other male reporters, have investigated missing girls in China, the UN’s role in perpetuating the spread of AIDS through breastfeeding in Africa, and oppression of women in the developing world.

Today there is generally a greater awareness of the inequities women face around the world thanks to the work of both men and, increasingly, women reporters. Journalism and readers are better off for this richer, more balanced perspective. But the numbers show that journalism still needs more women’s voices in foreign news stories, more investigative reporting into women’s issues, and more prizes in recognition of those investigations, so that women’s ideas are finally equated with men’s ideas. Giving female correspondents recognition gives them authority and power, amplifying the voices of half the world's population, and the correspondents who are most likely to broadcast them. This is not just good for women—it's good for the world.